It took only a few hundred years for humans to wipe out 50 million years of evolution on New Zealand

Long before people arrived in New Zealand, it was dominated by multitudes of unique birds. They were absolutely everywhere: big birds, little birds, colorful birds, flightless birds. In the absence of reptilian and mammalian predators, birds evolved to fill every available niche, from giant moas that stood 11 feet tall and weighed as much as 230 kilograms (510 pounds) that were the ecological equivalent of deer and antelopes, to the largest eagle that ever lived, which was New Zealand’s apex predator, functioning similarly to lions and tigers and other big cats.

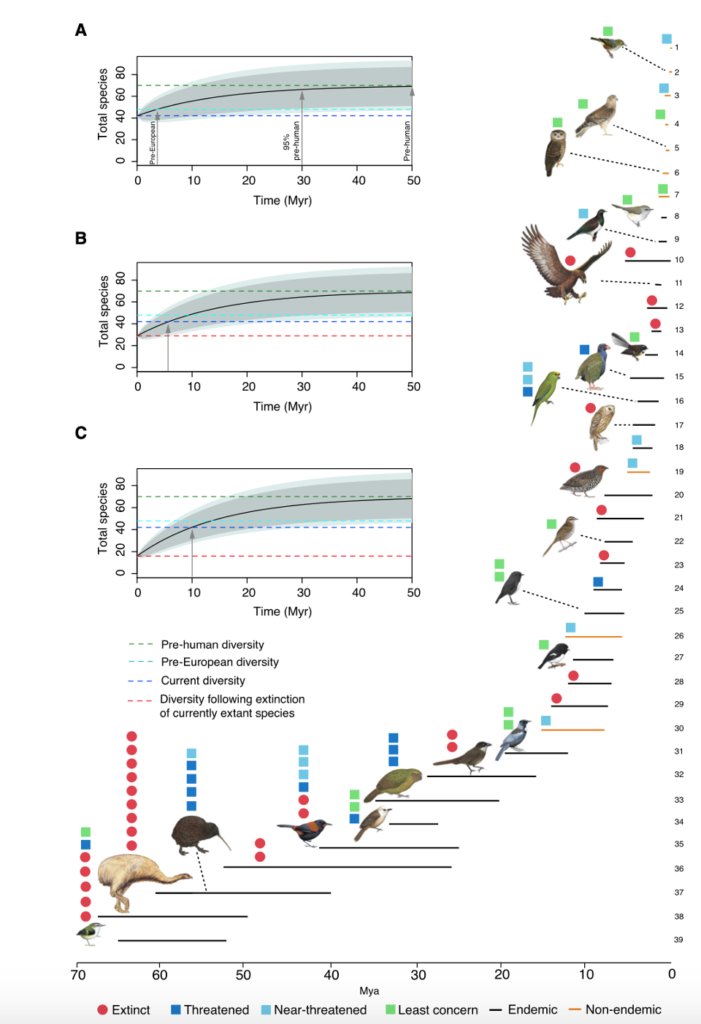

But after humans arrived 700 years ago, it took us only a few hundred years to drive more than half of New Zealand’s bird species into extinction, and more than 30% of the birds that survived our original onslaughts are threatened with extinction today. Nearly two-thirds could be under threat in the future. Considering these dire circumstances, an international team of scientists wondered how long it might take for New Zealand to recover its full diversity of bird species lost to human actions. According to their recently published study, the researchers estimated this process would take approximately 50 million years (50Ma). Further, they found that, if bird species that are currently threatened are allowed to go extinct, it would take an additional 10Ma for New Zealand to achieve today’s (severely compromised) level of species diversity.

“The conservation decisions we make today will have repercussions for millions of years to come”, said the lead author of the study, Luis Valente, a Research Associate at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin. “Some people believe that if you leave nature alone it will quickly recuperate, but the reality is that, at least in New Zealand, nature would need several million years to recover from human actions — and perhaps will never really recover.”

New Zealand’s avian diversity arose after many millions of years of evolution

New Zealand is home to a collection of odd birds, including the wrybill, a small shorebird whose bill curves sideways; the iconic kiwis, whose feathers resemble fur and which are the only bird species in the world to have nostrils at the tip of their beak; the flightless kakapo, which resembles a large moss-colored owl and is the heaviest parrot alive today; and of course, the kea, which is the world’s only alpine parrot and who is pushing the boundaries of our understanding of how astonishingly clever parrots can be. Despite this modern surfeit of avian biodiversity, it is just a mere whisper of what once lived on New Zealand, which was the result of many millions of years of evolutionary history.

But extinctions caused by human activities are erasing this history. Dr Valente and his collaborators note in their study that humans not only harm native wildlife by hunting them down and killing them, but also by developing the land they live on, and by introducing invasive species that out-compete native wildlife. Whilst introduced species may make up for numeric losses of native wildlife, they usually do so without providing any essential ecosystem services.

Islands are ideal places to study both speciation and extinction

The Maori arrived on New Zealand around 700 years ago, followed by European settlers less than 250 years ago. The arrival of people heralded one of the largest extinction waves ever documented, where almost half of all the native avifauna quickly went extinct. Entire taxonomic families were wiped out. Whilst the number of lost or threatened island bird species has been quantified, the broad-scale evolutionary consequences of human impacts on island biodiversity have rarely been measured.

Dr Valente, who uses evolutionary modelling and molecular phylogenetics to study island biogeography, wanted to develop a method to estimate how long it would take an island to regain the number of species it had prior to human arrival. Considering the history of New Zealand, Dr Valente and his collaborators, Rampal Etienne, a professor at the University of Groningen and Naturalis Biodiversity Centre in the Netherlands, and evolutionary ecologist Juan C. Garcia-R, a junior research officer in the veterinary school at Massey University in New Zealand, recognized it was the ideal model system for this task.

In their recent study, Dr Valente and his collaborators wanted to answer two basic questions: “how far have humans perturbed this unique and isolated biological assembly from its natural state?” and “how deep will the evolutionary impact be if currently threatened species go extinct?”

“The anthropogenic wave of extinction in New Zealand is very well documented, due to decades of paleontological and archaeological research”, Dr Valente said in a statement. “Also, previous studies have produced dozens of DNA sequences for extinct New Zealand birds, which were essential to build datasets needed to apply our method.”

Dr Valente and his collaborators’ method was straightforward. First, they compiled a complete dataset of New Zealand’s native and resident land birds. This dataset was then used in computer analyses — a model they named DAISIE (dynamic assembly of islands through speciation, immigration, and extinction). By combining DAISIE with statistical models to assess speciation rates, they estimated how long it would take, on average, for bird diversity to reach pre-human levels in New Zealand.

The data revealed it would take approximately 50 million years to recover the number of species lost. Further, the data showed that, if all species that are currently under threat are allowed to go extinct, it would require an additional 10 million years of evolutionary time to return to the species numbers of today.

Compare these numbers to when humans first arose, which was somewhere between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago: the time it will take New Zealand’s avifauna to recover from the damage we’ve done — and could still do — is 250 times longer than the human species has been in existence.

“Islands are at the frontline of the anthropogenic extinction crisis”, Dr Valente and his collaborators wrote in the study. “A vast number of island birds have gone extinct since human colonization, and an important proportion is currently threatened with extinction.”

New Zealand, whose government consists of responsible, thinking adults, is taking this threat to their endemic avifauna seriously.

“The conservation initiatives currently being undertaken in New Zealand are highly innovative and appear to be efficient and may yet prevent millions of years of evolution from further being lost”, Dr Valente said.

Dr Valente and his collaborators are already working to estimate evolutionary return times for several other islands to identify which may have been under threat longer. They also are looking to identify which anthropogenic effects play the most significant role in driving species losses.

“We hope the measure of future potential evolutionary time lost may help promote and guide conservation efforts in some of the world’s most unique biological assemblies”, the authors wrote in their study.

![Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*] Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*]](https://tahav.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Hotstar-Premium-Cookies-Free-100x70.jpg)