It’s a milestone in the effort to commercialize space. But for Musk’s company, SpaceX, it’s also the latest milestone in a wild ride that began with epic failures and the threat of bankruptcy.

It all started with the dream of growing a rose on Mars.

That vision, Elon Musk‘s vision, morphed into a shake-up of the old space industry, and a fleet of new private rockets. Now, those rockets will launch Nasa astronauts from Florida to the International Space Station — the first time a for-profit company will carry astronauts into the cosmos.

It’s a milestone in the effort to commercialize space. But for Musk’s company, SpaceX, it’s also the latest milestone in a wild ride that began with epic failures and the threat of bankruptcy.

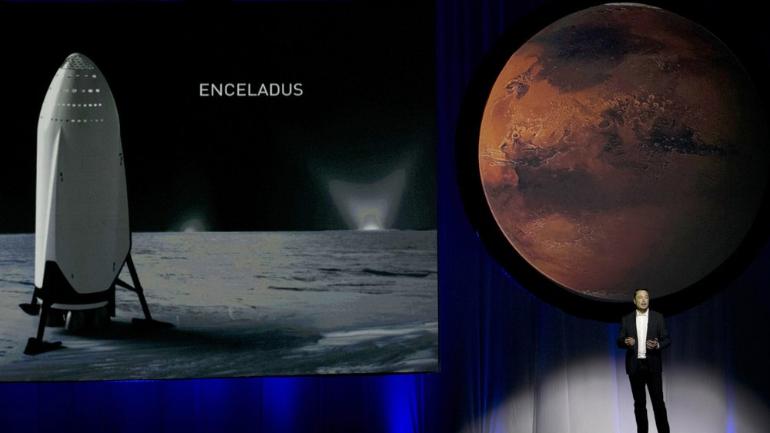

If the company’s eccentric founder and CEO has his way, this is just the beginning: He’s planning to build a city on the red planet, and live there.

“What I really want to achieve here is to make Mars seem possible, make it seem as though it’s something that we can do in our lifetimes and that you can go,” Musk told a cheering congress of space professionals in Mexico in 2016.

Musk “is a revolutionary change” in the space world, says Harvard University astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell, whose Jonathan’s Space Report has tracked launches and failures for decades.

Ex-astronaut and former Commercial Spaceflight Federation chief Michael Lopez-Alegria says, “I think history will look back at him like a da Vinci figure.”

Musk has become best known for Tesla, his audacious effort to build an electric vehicle company. But SpaceX predates it.

At 30, Musk was already wildly rich from selling his internet financial company PayPal and its predecessor Zip2. He arranged a series of lunches in Silicon Valley in 2001 with G. Scott Hubbard, who had been Nasa’s Mars czar and was then running the agency’s Ames Research Center.

Musk wanted to somehow grow a rose on the red planet, show it to the world and inspire school children, recalls Hubbard.

“His real focus was having life on Mars,” says Hubbard, a Stanford University professor who now chairs SpaceX’s crew safety advisory panel.

The big problem, Hubbard told him, was building a rocket affordable enough to go to Mars. Less than a year later Space Exploration Technologies, called SpaceX, was born.

There are many space companies and like all of them, SpaceX is designed for profit. But what’s different is that behind that profit motive is a goal, which is simply to “Get Elon to Mars,” McDowell says. “By having that longer-term vision, that’s pushed them to be more ambitious and really changed things.”

Everyone at SpaceX, from senior vice presidents to the barista who offers its in-house cappuccinos and FroYo, “will tell you they are working to make humans multi-planetary,” says former SpaceX Director of Space Operations Garrett Reisman, an ex-astronaut now at the University of Southern California.

Musk founded the company just before Nasa ramped up the notion of commercial space.

Traditionally, private firms built things or provided services for Nasa, which remained the boss and owned the equipment. The idea of bigger roles for private companies has been around for more than 50 years, but the market and technology weren’t yet right.

Nasa’s two deadly space shuttle accidents — Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003 — were pivotal, says W. Henry Lambright, a professor of public policy at Syracuse University.

When Columbia disintegrated, Nasa had to contemplate a post-space shuttle world. That’s where private companies came in, Lambright says.

After Columbia, the agency focused on returning astronauts to the moon, but still had to get cargo and astronauts to the space station, says Sean O’Keefe, who was Nasa’s administrator at the time. A 2005 pilot project helped private companies develop ships to bring cargo to the station.

SpaceX got some of that initial funding. The company’s first three launches failed. The company could have just as easily failed too, but Nasa stuck by SpaceX and it started to pay off, Lambright says.

“You can’t explain SpaceX without really understanding how Nasa really kind of nurtured it in the early days,” Lambright says. “In a way, SpaceX is kind of a child of Nasa.”

Since 2010, Nasa has spent $6 billion to help private companies get people into orbit, with SpaceX and Boeing the biggest recipients, says Phil McAlister, Nasa’s commercial spaceflight director.

Nasa plans to spend another $2.5 billion to purchase 48 astronaut seats to the space station in 12 different flights, he says. At a little more than $50 million a ride, it’s much cheaper than what Nasa has paid Russia for flights to the station.

Starting from scratch has given SpaceX an advantage over older firms and Nasa that are stuck using legacy technology and infrastructure, O’Keefe says.

And SpaceX tries to build everything itself, giving the firm more control, Reisman says. The company saves money by reusing rockets, and it has customers aside from Nasa.

The California company now has 6,000 employees. Its workers are young, highly caffeinated and put in 60- to 90-hour weeks, Hubbard and Reisman say. They also embrace risk more than their Nasa counterparts.

Decisions that can take a year at Nasa can be made in one or two meetings at SpaceX, says Reisman, who still advises the firm.

In 2010, a Falcon 9 rocket on the launch pad had a cracked nozzle extension on an engine. Normally that would mean rolling the rocket off the pad and a fix that would delay launch more than a month.

But with Nasa’s permission, SpaceX engineer Florence Li was hoisted into the rocket nozzle with a crane and harness. Then, using what were essentially garden shears, she “cut the thing, we launched the next day and it worked,” Reisman says.

Musk is SpaceX’s public and unconventional face — smoking marijuana on a popular podcast, feuding with local officials about opening his Tesla plant during the pandemic, naming his newborn child “X Æ A-12.” But insiders say aerospace industry veteran Gwynne Shotwell, the president and chief operating officer, is also key to the company’s success.

“The SpaceX way is actually a combination of Musk’s imagination and creativity and drive and Shotwell’s sound management and responsible engineering,” McDowell says.

But it all comes back to Musk’s dream. Former Nasa chief O’Keefe says Musk has his eccentricities, huge doses of self-confidence and persistence, and that last part is key: “You have the capacity to get through a setback and look … toward where you’re trying to go.”

![Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*] Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*]](https://tahav.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Hotstar-Premium-Cookies-Free-100x70.jpg)