The fast-growing list of possible treatments for the novel coronavirus includes an unlikely candidate: famotidine, the active compound in the over-the-counter heartburn drug Pepcid. On 7 April, the first COVID-19 patients at Northwell Health in the New York City area began receiving famotidine intravenously, at nine times the heartburn dose. Unlike other drugs the 23-hospital system is testing, including Regeneron’s sarilumab and Gilead Science’s remdesivir, Northwell kept the famotidine study under wraps to secure a research stockpile before other hospitals, or even the federal government, started buying it. “If we talked about this to the wrong people or too soon, the drug supply would be gone,” says Kevin Tracey, a former neurosurgeon in charge of the hospital system’s research.

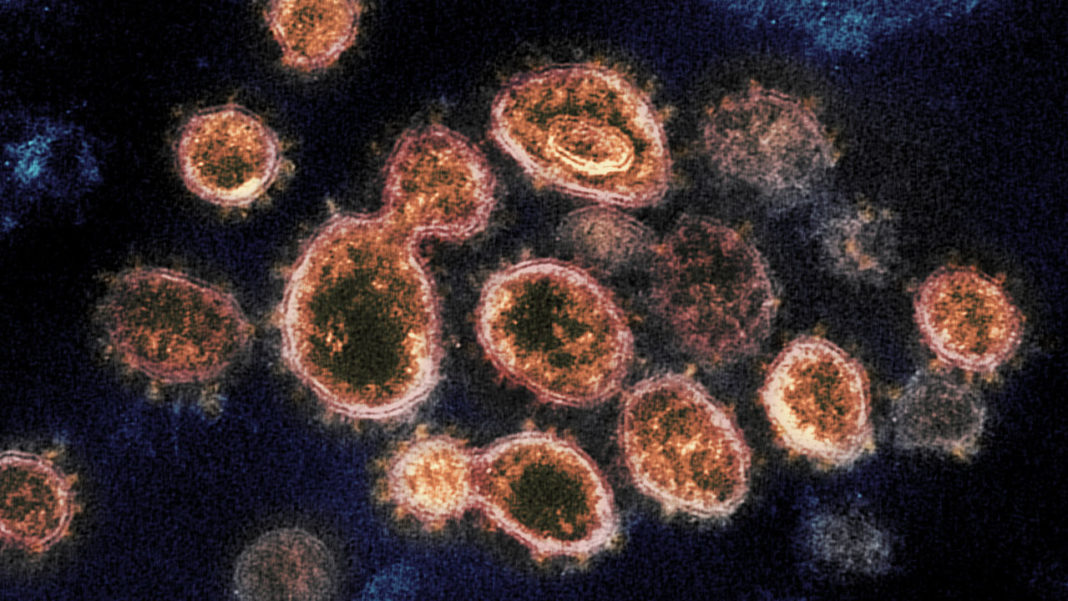

As of Saturday, 187 COVID-19 patients in critical status, including many on ventilators, have been enrolled in the trial, which aims for a total of 1174 people. Reports from China and molecular modeling results suggest that the drug, which seems to bind to a key enzyme in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), could make a difference. But the hype surrounding hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine—the unproven antimalarial drugs touted by President Donald Trump and some physicians and scientists—has made Tracey wary of sparking premature enthusiasm. He is tight-lipped about famotidine’s prospects, at least until interim results from the first 391 patients are in. “If it does work, we’ll know in a few weeks,” he says.

A globe-trotting infectious disease doctor named Michael Callahan was the first to call attention to the drug in the United States. Callahan, who is based at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and has extensive connections in the biodefense world, has spent time in disease hot zones around the world, including the 2003 outbreak of another coronavirus disease, SARS, in Hong Kong. In mid-January, he was in Nanjing, China, working on an avian flu project. As the COVID-19 epidemic began exploding in Wuhan, he followed his Chinese colleagues to the increasingly desperate city.

The virus was killing as many one out of five patients over 80 years of age. Patients of all ages with hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were faring poorly. Callahan and his Chinese colleagues got curious about why many of the survivors tended to be poor. “Why are these elderly peasants not dying?” he asks.

In reviewing 6212 COVID-19 patient records, the doctors noticed that many survivors had been suffering from chronic heartburn and were on famotidine rather than more-expensive omeprazole (Prilosec), the medicine of choice both in the United States and among wealthier Chinese. Hospitalized COVID-19 patients on famotidine appeared to be dying at a rate of about 14% compared with 27% for those not on the drug, although the analysis was crude and the result was not statistically significant.

But that was enough for Callahan to pursue the issue back home. After returning from Wuhan, he briefed Robert Kadlec, assistant secretary for Preparedness and Response at the Department of Health and Human Services, then checked in with Robert Malone, chief medical officer of Florida-based Alchem Laboratories, a contract manufacturing organization. Malone is part of a classified project called DOMANE that uses computer simulations, artificial intelligence, and other methods to rapidly identify U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs and other safe compounds that can be repurposed against threats such as new viruses.

Malone had his eyes on a viral enzyme called the papainlike protease, which helps the pathogen replicate. To see if famotidine binds to the protein, he would ordinarily need the enzyme’s 3D structure, but that would not be available for months. So Malone recruited computational chemist Joshua Pottel, president of Montreal-based Molecular Forecaster, to predict it from two crystal structures of the protease from the 2003 SARS coronavirus, combined with the new coronavirus’s RNA sequence.

It was hardly plug-and-play. Among other things, they compared the gene sequences of the new and old proteases to rule out crucial differences in structure. Pottel then tested how 2600 different compounds interact with the new protease. The modeling yielded several dozen promising hits that pharmaceutical chemists and other experts narrowed to three. Famotidine was one. (The compound has not popped up in in vitro screens of existing drug libraries for antiviral activity, however.)

With both the tantalizing Chinese data and the modeling pointing towards famotidine, a low-cost, generally safe drug, Callahan contacted Tracey about running a double-blind randomized study. COVID-19 patients with decreased kidney function would be excluded because high doses of famotidine can cause heart problems in them.

After getting Food and Drug Administration approval, Northwell used its own funds to launch the effort. Just getting half of the needed famotidine in sterile vials took weeks, because the injectable version is not widely used. On 14 April, the U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which operates under Kadlec, gave Alchem a $20.7 million contract for the trial, most of which paid Northwell’s costs.

The study’s draft protocol was aimed only at evaluating famotidine’s efficacy, but Trump’s “game-changer” antimalarial drug was rapidly becoming the standard of care for hospitalized COVID-19 patients. That meant investigators would only be able to recruit enough subjects for a trial that tested a combination of famotidine and hydroxychloroquine. Those patients would be compared with a hydroxychloroquine-only arm and a historic control arm made up of hundreds of patients treated earlier in the outbreak. “Is it good science? No,” Tracey says. “It’s the real world.”

Anecdotal evidence has encouraged the Northwell researchers. After speaking to Tracey, David Tuveson, director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Cancer Center, recommended famotidine to his 44-year-old sister, an engineer with New York City hospitals. She had tested positive for COVID-19 and developed a fever. Her lips became dark blue from hypoxia. She took her first megadose of oral famotidine on 28 March. The next morning, her fever broke and her oxygen saturation returned to a normal range. Five sick coworkers, including three with confirmed COVID-19, also showed dramatic improvements upon taking over-the-counter versions of the drug, according a spreadsheet of case histories Tuveson shared with Science. Many COVID-19 patients recover with simple symptom-relieving medications, but Tuveson credits the heartburn drug. “I would say that was a penicillin effect,” he says.

After an email chain about Tuveson’s experience spread widely among doctors, Timothy Wang, head of gastroenterology at Columbia University Medical Center, saw more hints of famotidine’s promise in his own retrospective review of records from 1620 hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Last week, he shared the results with Tracey and Callahan, and he added them as a co-authors on a paper now under review at Annals of Internal Medicine. All three researchers emphasize, though, that the real test is the trial now underway. “We still don’t know if it will work or not,” Tracey says.

Callahan has kept busy since his return from China. Kadlec deployed him on medical evacuation missions of Americans on two heavily infected cruise ships. Now back to doing patient rounds in Boston, he says the famotidine lead underscores the importance of science diplomacy in the face of an infectious disease that knows no borders. When it comes to experience with COVID-19, he says, “No amount of smart people at the [National Institutes of Health] or Harvard or Stanford can outclass an average doctor in Wuhan.”

![Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*] Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*]](https://tahav.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Hotstar-Premium-Cookies-Free-100x70.jpg)