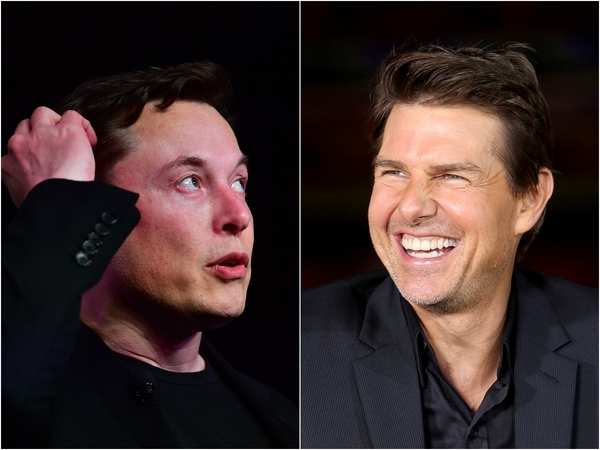

If their plan falls into place, the Russians are expected to beat Mission Impossible star Tom Cruise and Hollywood director Doug Liman, who were first to announce their project together with NASA and Space X, the company of billionaire Elon Musk.

Six decades after Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit Earth, earning Moscow a key win in the Cold War, Russia is again in a space race with Washington.

This time though the stakes are somewhat glitzier.

On October 5, one of Russia’s most celebrated actresses, 36-year-old Yulia Peresild is blasting off to the International Space Station (ISS) with film director Klim Shipenko, 38.

Their mission? Shoot the first film in orbit before the Americans do.

If their plan falls into place, the Russians are expected to beat Mission Impossible star Tom Cruise and Hollywood director Doug Liman, who were first to announce their project together with NASA and Space X, the company of billionaire Elon Musk.

“I really want us to be not only the first but also the best,” Peresild told AFP, with the clock ticking down to the planned October 5 blast-off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

The Call — the Russian project’s working title — was announced in September last year, four months after the Hollywood project.

But apart from its grand ambitions, little is known about the film.

Doctor who?

Its plot, which has been kept under wraps by the crew and Russia’s space agency, has been revealed by Russian media outlets to feature a doctor dispatched urgently to the ISS to save a cosmonaut.

Nor has The Call’s budget been disclosed. But it’s no secret that travel to space is a costly business: one seat on a Soyuz rocket to the ISS usually costs NASA tens of millions of dollars.

Hinting at the film’s aesthetic direction, one big name on the credit list is Konstantin Ernst, the 60-year-old head of the overtly Kremlin-friendly Channel One television network.

Ernst has stage-managed some of the most important moments in Russia’s recent political history and of President Vladimir Putin’s career: military parades, inaugurations, the opening ceremony of the 2014 Olympic Games in Sochi.

Dmitry Rogozin, the outspoken head of Russia’s Roscosmos space agency, will also feature when the credits role in theatres throughout the country.

He is not known for prominence in the film industry, but rather for presiding over an agency plagued by stagnation and corruption — and for publicly sparring with Musk on Twitter.

‘Propaganda tool’

For Rogozin, 57, the film is a way to project stature as Roscosmos loses ground in technological advancement to US rivals.

But it is also part of a geopolitical battle his country is engaged in with Washington, according to a recent interview he gave to a Moscow tabloid.

“Cinema was long ago turned into a powerful propaganda tool,” he told popular daily Komsomolskaya Pravda in June.

His assessment of the role of film comes at a time when the relationship between Moscow and Washington has frayed to the point of resembling the standoff of the Cold War.

Rogozin said in the interview that Cruise and Liman had initially approached Roscosmos in early 2020 to collaborate on the film.

But, he said, unnamed “political forces” pressured them to give up on the idea of working with the Russians.

“I understood after this that space is big politics,” he told the paper. “It was then that an idea appeared to make the film”.

Representatives of Cruise did not respond to AFP requests for comment.

‘Not a superhero’

In preparation for this 21st-century space race, Peresild has since late May been undergoing intensive training at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre in Star City outside Moscow.

When she spoke to AFP, she had already managed the centrifuge and would be getting trained in how to survive in hostile environments for when she plummets back to Earth in a Soyuz capsule on October 17.

Still, she is focused on the task at hand.

The tiny film set of the ISS will be a challenging space in which to work, particularly for the director, who will also handle the cameras, lighting, sound and make-up.

“We will have to film in space what it is not possible to shoot on Earth,” she says.

Peresild said that unlike many other Soviet children who grew up with Gagarin’s feats looming large, she never dreamed of going to space.

She admits to feeling “afraid” when she was selected for the job from a pool of 3,000 candidates.

“I am not a superhero,” she told AFP.

She said she had drawn inspiration from children involved in her Galchonok foundation that supports young people with disabilities.

“For them, picking up a spoon is like going to space for me.”

They “must believe in the impossible”.

![Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*] Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*]](https://tahav.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Hotstar-Premium-Cookies-Free-100x70.jpg)