Largest solar telescope in the world shows boiling plasma on the solar surface

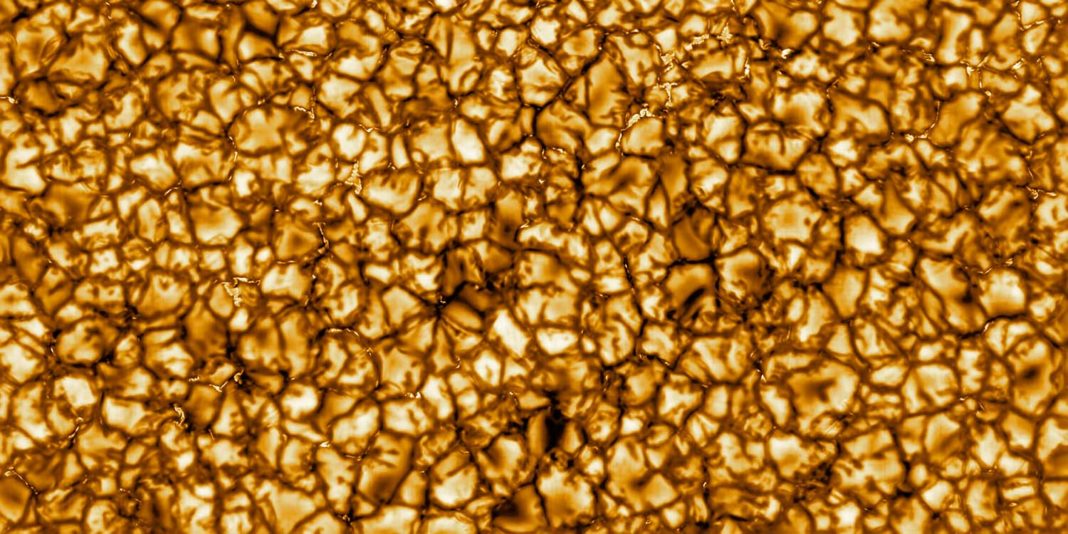

Hot plasma churns on the sun with newfound precision in the first images from the largest solar telescope in the world.

The National Science Foundation’s 4-meter-wide Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope — named after the late senator from Hawaii — is still under construction on Maui, but that hasn’t stopped researchers from pointing it at the sun to see if it’s working. These “first-light” images, released January 29, reveal features on the sun’s surface just 30 kilometers across, or about three times as small as anything yet seen.

“We have now seen the smallest details on the largest object in the solar system,” said Inouye telescope director Thomas Rimmele during a January 24 news teleconference.

Covering an area 36,500 kilometers across — roughly three times the diameter of Earth — the images show familiar bubbles of plasma percolating up from the depths. In the dark lanes between the bubbles, newly resolved clusters of bright points appear at the roots of magnetic fields that stretch out into space.

The telescope is being built to study magnetic structures that may lead to new insights into why the corona, the sun’s outer atmosphere, is millions of degrees hotter than the surface, and what drives space weather that occasionally interferes with technology on Earth (SN: 3/7/19).

The observatory is being built on the summit of Haleakala, which appropriately translates to “house of the sun.” When science operations start in July, it will complete a trifecta of new sun-gazing facilities, joining NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which is circling closer and closer to the sun (SN: 12/4/19), and ESA’s Solar Orbiter, scheduled to launch in February on a journey that will take it over the sun’s north and south poles.

Each of these facilities will bring something different to solar exploration. Solar Orbiter will watch the sun from a unique vantage point, while Parker snuggles up close and directly samples the plasma and magnetic fields. Inouye, thanks to its large mirror, will bring an unmatched clarity of detail, and by being on the ground, researchers can easily adapt it to new questions that will inevitably arise.

As director of the NSF’s National Solar Observatory, Valentin Pillet, observed: “It really is a great time to be a solar astronomer.”

![Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*] Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*]](https://tahav.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Hotstar-Premium-Cookies-Free-100x70.jpg)