A Canadian start-up, GHGSat, is promising to release a high-resolution map of methane in Earth’s atmosphere by the year’s end.

The company has one spacecraft in orbit currently to monitor the trace gas. Another two are expected to go up in the next few months.

Montreal-based GHGSat tracks oil and gas operations, alerting owners to any leaks of methane from their facilities.

The global map should make its debut at November’s big UN climate conference.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, and like carbon dioxide is increasing its concentration in the atmosphere. Quite why that is, though, is not fully understood.

Emissions associated with fossil-fuel use are a major factor, but there are also many natural sources of the gas that require a more complete explanation.

While GHGSat is focused on selling observations of methane, it believes it can also make a very useful contribution to open science with its planned free-to-use visualisation.

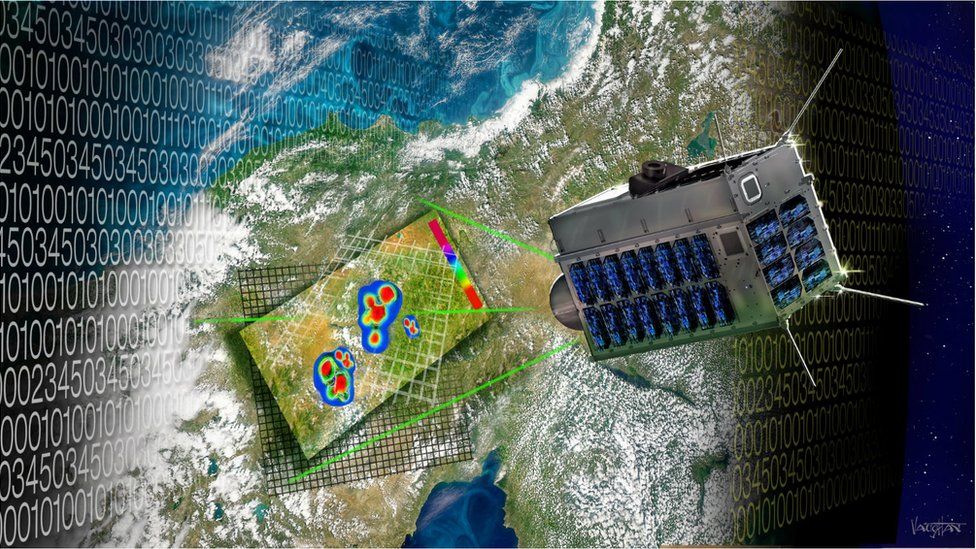

The company’s first satellite, launched in 2016, delivers 12km by 12km spot measurements of methane in the air. Features larger than 50m across can be sensed.

The soon-to-fly spacecraft are designed with finer vision still, with a resolution of 25m per pixel.

To make the visualisation, GHGSat says its analytics team will combine the firm’s own satellites’ observations with all other publicly available datasets.

These include the measurements of methane gathered by the big space agencies and from ground sensors.

The resulting map will be unveiled in the UK next November at “COP26”, the Glasgow conference where world leaders will be expected to come up with plans for deeper cuts in the gases that heat the planet.

“This free visualisation will be on a grid averaging 2km by 2km over land all around the world. That pretty much will be the state of the art when it comes to the visualisation of methane,” said GHGSat President and CEO, Stephane Germain.

“Certainly, it will be complementary to what existing systems are doing, such as the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF); and the European Space Agency (Esa) with its Tropomi satellite, of course.

“They’re doing things on a larger scale globally, and they’re in the forecasting business as well. We’re not going to try to do that; we are simply going to be looking at concentrations on a rolling basis on a 2km grid-scale.”

In time, a visualisation of carbon dioxide concentrations will be added as well.

GHGSat is part of the wave of so-called “New Space” companies that are launching constellations of low-cost satellites. It aims to get 10 up by 2022.

This would give it monthly coverage of methane emissions from the entire shale gas industry in the United States.

The value of the observations made by GHGSat’s first spacecraft was demonstrated in a scientific paper last year in which an anomalous and persistent plume of methane was traced to a gas compressor station in western Turkmenistan. The operator was apparently unaware that there was a leak.

The plume was evident in the data of the Esa-managed Tropomi satellite (formally known as Sentinel-5P), but GHGSat with its tighter resolution was able to identify the point source.

Mr Germain said: “Satellites operated by the big space agencies are important to us because they tip and cue our satellites to go look at hotspots around the world more efficiently than if we’re just relying on known locations of industrial facilities and then just scanning them one at a time.

“So it’s a great collaboration – both at the business level because it makes us more efficient, but also at the scientific level because it allows us to collaborate and cross-verify between systems.”

Esa and GHGSat signed a Memorandum of Intent in September last year on an exchange of data.

GHGSat’s global methane visualisation project was announced this week in Davos, Switzerland, at the World Economic Forum.

![Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*] Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*]](https://tahav.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Hotstar-Premium-Cookies-Free-100x70.jpg)