The CHEOPS satellite will gather data on previously discovered planets outside the solar system

A new satellite devoted to gazing at planets orbiting other stars has just launched into space.

At 3:54 a.m. Eastern time on December 18, the European Space Agency’s CHEOPS satellite lifted off from Kourou, French Guiana. CHEOPS — an abbreviation of “Characterizing Exoplanet Satellite” — is the first ESA-led mission dedicated solely to the study of planets outside the solar system. The launch was originally scheduled for December 17 but was called off shortly before takeoff due to a glitch with the rocket.

Unlike many other exoplanet missions, CHEOPS is not setting out to look for new planets. Rather, it will gather data on exoplanets already found, helping researchers figure out how these worlds were built.

While orbiting Earth, CHEOPS will spend 3½ years looking beyond our solar system for exoplanetary transits: subtle dips in starlight that occur when a planet crosses in front of its sun. The bigger the planet, the more starlight it blocks. By measuring how much the star darkens, researchers will be able to deduce the planet’s girth.

The focus will be to precisely measure the sizes of roughly 500 planets orbiting relatively bright stars. By combining the sizes with measurements of mass — obtained by ground-based telescopes that record how fast a host star gets whipped around by a planet’s gravity — astronomers will be able to calculate each planet’s density, a key metric for figuring out what these planets are made of. Astronomers will also look for hints of atmospheres by tracking how quickly the starlight dims just before and after a transit.

And there’s always the chance that some unexpected planets will wander in front of their stars while CHEOPS is watching.

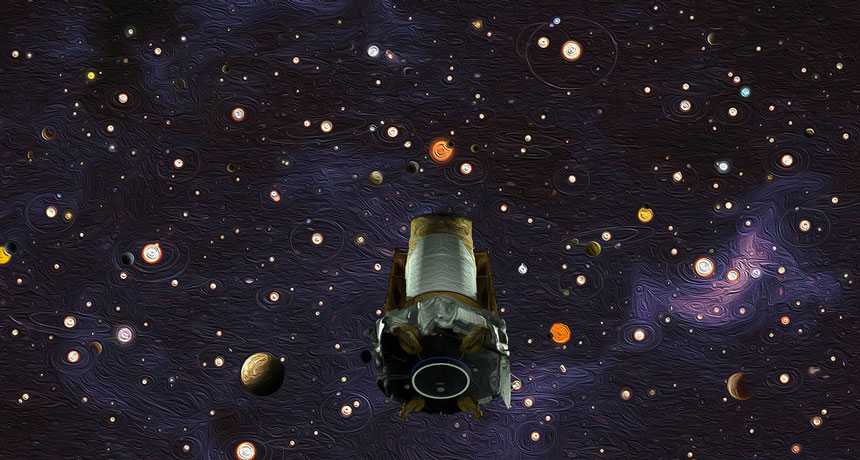

Transit-hunting is the same technique used by the now-defunct Kepler spacecraft (SN: 10/30/18) and the ongoing TESS mission (SN: 1/8/19), though CHEOPS has the advantage of knowing exactly when to look for a transit. While the worlds found by Kepler orbit stars that are too faint for CHEOPS to follow up, many planets discovered by TESS are just right, and the two teams are partnering up.

“There is a lot of synergy and complementarity between the two missions,” says Willy Benz, an astronomer at the University of Bern in Switzerland, who leads the CHEOPS science team.

![Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*] Hotstar Premium Cookies 2019 [*100% Working & Daily Updated*]](https://tahav.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Hotstar-Premium-Cookies-Free-100x70.jpg)